“The map of Kenya’s maize-growing regions mirrors the map of the nation’s acid soils.”

So says Dickson Ligeyo, senior research officer at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO; formerly the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute, or KARI), who believes this paints a sombre picture for his country’s maize farmers.

Maize is a staple crop for Kenyans, with 90 percent of the population depending on it for food. However, acid soils cause yield losses of 17–50 percent across the nation.

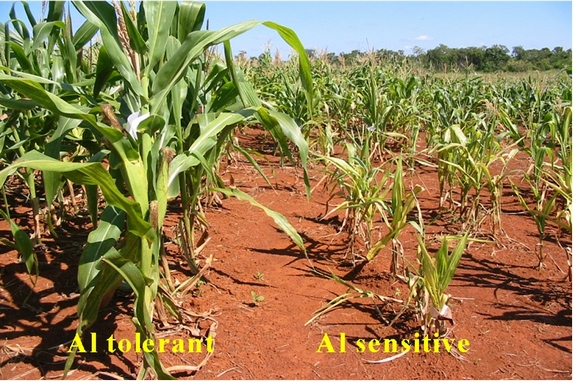

Soil acidity is a major environmental and economic concern in many more countries around the world. The availability of nutrients in soil is affected by pH, so acid conditions make it harder for plants to get a balanced diet. High acidity causes two major problems: perilously low levels of phosphorus and toxically high levels of aluminium. Aluminium toxicity affects 38 percent of farmland in Southeast Asia, 31 percent in Latin America and 20 percent in East Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and North America.

Aluminium toxicity in soil comes close to rivalling drought as a food-security threat in critical tropical food-producing regions. By damaging roots, acid soils deprive plants of the nutrients and water they need to grow – a particularly bitter effect when water is scarce.

Maize, meanwhile, is one of the most economically important food crops worldwide. It is grown in virtually every country in the world, and it is a staple food for more than 1.2 billion people in developing countries across sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. In many cultures it is consumed primarily as porridge: polenta in Italy; angu in Brazil; and isitshwala, nshima, pap, posho,sadza or ugali in Africa.

Maize is also a staple food for animals reared for meat, eggs and dairy products. Around 60 percent of global maize production is used for animal feed.

The world demand for maize is increasing at the same time as global populations burgeon and climate changes. Therefore, improving the ability of maize to withstand acid soils and produce higher yields with less reliable rainfall is paramount. This is why the CGIAR Generation Challenge Programme (GCP) invested almost USD 12.5 million into maize research between 2004 and 2014.

GCP’s goal was to facilitate the use of genetic diversity and advanced plant science to improve food security in developing countries through the breeding of ‘super’ crops – including maize – able to tolerate drought and poor soils and resist diseases.

Researchers take on the double whammy of acid soils and drought

Part of successfully breeding higher-yielding drought-tolerant maize varieties involves improving plant genetics for acid soils. In these soils, aluminium toxicity inhibits root growth, reducing the amount of water and nutrients that the plant can absorb and compounding the effects of drought.

Improving plant root development for aluminium tolerance and phosphorous efficiency can therefore have the positive side effect of higher plant yield when water is limited.

A farmer in Tanzania shows the effects of drought on her maize crop. The maize ears are undersized with few grains.

Although plant breeders have exploited the considerable variation in aluminium tolerance between different maize varieties for many years, aluminium toxicity has been a significant but poorly understood component of plant genetics. It is a particularly complex trait in maize that involves multiple genes and physiological mechanisms.

The solution is to take stock of what maize germplasm is available worldwide, characterise it, clone the sought-after genes and implement new breeding methods to increase diversity and genetic stocks.

Scientists join hands to unravel maize complexity

Scientists from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) got their heads together between 2005 and 2008 to itemise what maize stocks were available.

Marilyn Warburton, then a molecular geneticist at CIMMYT, led this GCP-funded project. Her goal was to discover how all the genetic diversity in maize gene-bank collections around the globe might be used for practical plant improvement. She first gathered samples from gene banks all over the world, including those of CIMMYT and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). Scientists from developing country research centres in China, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Nigeria, Thailand and Vietnam also contributed by supplying DNA from their local varieties.

Researchers then used molecular markers and a bulk fingerprinting method – which Marilyn was instrumental in developing – for three purposes: to characterise the structure of maize populations, to better understand how maize migrated across the world, and to complete the global picture of maize biodiversity. Scientists were also using markers to search for new genes associated with desirable traits.

Allen Oppong, a maize pathologist and breeder from Ghana’s Crops Research Institute (CRI), of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, was supported by GCP from 2007 to 2010 to characterise Ghana’s maize germplasm. Trained in using the fingerprinting technique, Allen was able to identify distinctly different maize germplasm in the north of Ghana (with its dry savanna landscape) and in the south (with its high rainfall). He also identified mixed germplasm, which he says demonstrates that plant germplasm often finds its way to places where it is not suitable for optimal yield and productivity. Maize yields across the country are low.

Stocktaking a world’s worth of maize for GCP was a challenge, but not the only one, according to Marilyn. “In the first year it was hard to see how all the different partners would work together. Data analysis and storage was the hardest; everyone seemed to have their own idea about how the data could be stored, accessed and analysed best.

“The science was also evolving, even as we were working, so you could choose one way to sequence or genotype your data, and before you were even done with the project, a better way would be available,” she recalls.

Comparing genes: sorghum gene paves way for maize aluminium tolerance

In parallel to Marilyn’s work, scientists at the Brazilian Corporation of Agricultural Research (EMBRAPA) had already been advancing research on plant genetics for acid soils and the effects of aluminium toxicity on sorghum – spurred on by the fact that almost 70 percent of Brazil’s arable land is made up of acid soils.

What was of particular interest to GCP in 2004 was that the Brazilians, together with researchers at Cornell University in the USA, had recently mapped and identified the major sorghum aluminium tolerance locus AltSB, and were working on isolating the major gene within it with a view to cloning it. Major genes were known to control aluminium tolerance in sorghum, wheat and barley and produce good yields in soils that had high levels of aluminium. The gene had also been found in rape and rye.

GCP embraced the opportunity to fund more of this work with a view to speeding up the development of maize – as well as sorghum and rice – germplasm that can withstand the double whammy of acid soils and drought.

Maize trials in the field at EMBRAPA. The maize plants on the left are aluminium-tolerant and so able to withstand acid soils, while those on the right are not.

Leon Kochian, Director of the Robert W Holley Center for Agriculture and Health, United States Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Research Service and Professor at Cornell University, was a Principal Investigator for various GCP research projects investigating how to improve grain yields of crops grown in acid soils. “GCP was interested in our work because we were working with such critical crops,” he says.

“The idea was to use discoveries made in the first half of the GCP’s 10-year programme – use comparative genomics to look into genes of rice and maize to see if we can see relations in those genes – and once you’ve cloned a gene, it is easier to find a gene that can work for other crops.”

The intensity of GCP-supported maize research shifted up a gear in 2007, after the team led by Jurandir Magalhães, research scientist in molecular genetics and genomics of maize and sorghum at EMBRAPA, used positional cloning to identify the major sorghum aluminium tolerance gene SbMATE responsible for the AltSB aluminium tolerance locus. The team comprised researchers from EMBRAPA, Cornell, the Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences (JIRCAS) and Moi University in Kenya.

By combing the maize genome searching for a similar gene to sorghum’s SbMATE, Jurandir’s EMBRAPA colleague Claudia Guimarães and a team of GCP-supported scientists discovered the maize aluminium tolerance gene ZmMATE1. High expression of this gene, first observed in maize lines with three copies of ZmMATE1, has been shown to increase aluminium tolerance. ZmMATE1 improves grain yields in acid soil by up to one tonne per hectare when introgressed in an aluminium-sensitive line.

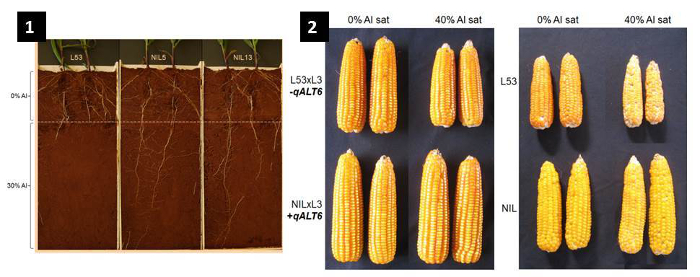

The genetic region, or locus, containing the ZmMATE1 aluminium tolerance gene is known as qALT6. Photo 1 shows a rhyzobox containing two layers of soil: a corrected top-soil and lower soils with 15 percent aluminium saturation. On the right, near-isogenic lines (NILs) introgressed with qALT6 show deeper roots and longer secondary roots in the acidic lower soil, whereas on the left the maize line without qALT6, L53, shows roots mainly confined to the corrected top soil. Photo 2 shows maize ears from lines without qALT6 (above) and with qALT6 (below); the lines with qALT6 maintain their size and quality even under high aluminium levels of 40 percent aluminium saturation.

The outcomes of these GCP-supported research projects provided the basic materials, such as molecular markers and donor sources of the positive alleles, for molecular-breeding programmes focusing on improving maize production and stability on acid soils in Latin America, Africa and other developing regions.

Kenya deploys powerful maize genes

One of those researchers crucial to achieving impact in GCP’s work in maize was Samuel (Sam) Gudu of Moi University, Kenya. From 2010 he was the Principal Investigator for GCP’s project on using marker-assisted backcrossing (MABC) to improve aluminium tolerance and phosphorous efficiency in maize in Kenya. This project combined molecular and conventional breeding approaches to speed up the development of maize varieties adapted to the acid soils of Africa, and was closely connected to the other GCP comparative genomics projects in maize and sorghum.

MABC is a type of marker-assisted selection (see box), which Sam’s team – including Dickson Ligeyo of KALRO – used to combine new molecular materials developed through GCP with Kenyan varieties. They have thus been able to significantly advance the breeding of maize varieties suitable for soils in Kenya and other African countries.

Maize and Comparative Genomics were two of seven Research Initiatives (RIs) where GCP concentrated on advancing researchers’ and breeders’ skills and resources in developing countries. Through this work, scientists have been able to characterise maize germplasm using improved trait observation and characterisation methods (phenotyping), implement molecular-breeding programmes, enhance strategic data management and build local human and infrastructure capacity.

The ultimate goal of the international research collaboration on comparative genomics in maize was to improve maize yields grown on acidic soils under drought conditions in Kenya and other African countries, as well as in Latin America. Seven institutes partnered up to for the comparative genomics research: Moi University, KALRO, EMBRAPA, Cornell University, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), JIRCAS and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI).

“Before funding by GCP, we were mainly working on maize to develop breeding products resistant to disease and with increased yield,” says Sam. “At that time we had not known that soil acidity was a major problem in the parts of Kenya where we grow maize and sorghum. GCP knew that soil acidity could limit yields, so in the work with GCP we managed to characterise most of our acid soils. We now know that it was one of the major problems for limiting the yield of maize and sorghum.

“The relationship to EMBRAPA and Cornell University is one of the most important links we have. We developed material much faster through our collaboration with our colleagues in the advanced labs. I can see that post-GCP we will still want to communicate and interact with our colleagues in Brazil and the USA to enable us to continue to identify molecular materials that we discover,” he says. Sam and other maize researchers across Kenya, including Dickson, have since developed inbred, hybrid and synthetic varieties with improved aluminium tolerance for acid soils, which are now available for African farmers.

“We crossed them [the new genes identified to have aluminium tolerance] with our local material to produce the materials we required for our conditions,” says Sam.

“The potential for aluminium-tolerant and phosphorous-efficient material across Africa is great. I know that in Ethiopia, aluminium toxicity from acid soil is a problem. It is also a major problem in Tanzania. It is a major problem in South Africa and a major problem in Kenya. So our breeding work, which is starting now to produce genetic materials that can be used directly, or could be developed even further in these other countries, is laying the foundation for maize improvement in acid soils.”

Sam is very proud of the work: “Several times I have felt accomplishment, because we identified material for Kenya for the first time. No one else was working on phosphorous efficiency or aluminium tolerance, and we have come up with materials that have been tested and have become varieties. It made me feel that we’re contributing to food security in Kenya.”

Maize for meat: GCP’s advances in maize genetics help feed Asia’s new appetites

Reaping from the substantial advances in maize genetics and breeding, researchers in Asia were also able to enhance Asian maize genetic resources.

Bindiganavile Vivek, a senior maize breeder for CIMMYT based in India, has been working with GCP since 2008 on improving drought tolerance in maize, especially for Asia, for two reasons: unrelenting droughts and a staggering growth the importance of maize as a feedstock. This work was funded by GCP as part of its Maize Research Initiative.

“People’s diets across Asia changed after government policies changed in the 1990s. We had a more free market economy, and along with that came more money that people could spend. That prompted a shift towards a non vegetarian diet,” Vivek recounts.

“Maize, being the number one feed crop of the world, started to come into demand. From the year 2000 up to now, the growing area of maize across Asia has been increasing by about two percent every year. That’s a phenomenal increase. It’s been replacing other crops – sorghum and rice. There’s more and more demand.

“Seventy percent of the maize that is produced in Asia is used as feed. And 70 percent of that feed is poultry feed.”

In Vietnam, for example, the government is actively promoting the expansion of maize acreage, again displacing rice. Other Asian nations involved in the push for maize include China, Indonesia and The Philippines.

The problem with this growth is that 80 percent of the 19 million hectares of maize in South and Southeast Asia relies on rain as its only source of water, so is prone to drought: “Wherever you are, you cannot escape drought,” says Vivek. And resource-poor farmers have limited access to improved maize products or hybrids appropriate for their situation.

Vivek’s research for GCP focused on the development – using marker-assisted breeding methods, specifically marker-assisted recurrent selection (MARS) – of new drought-tolerant maize adapted to many countries in Asia. His goal was to transfer the highest expression of drought tolerance in maize into elite well-adapted Asian lines targeted at drought-prone or water-constrained environments.

Asia’s existing maize varieties had no history of breeding for drought tolerance, only for disease resistance. To make a plant drought tolerant, many genes have to be incorporated into a new variety. So Vivek asked: “How do you address the increasing demand for maize that meets the drought-tolerance issue?”

The recent work on advancing maize genetics for acid soils in the African and Brazilian GCP projects meant it was a golden opportunity for Vivek to reap some of the new genetic resources.

“This was a good opportunity to use African germplasm, bring it into India and cross it to some Asia-adapted material,” he says.

A key issue Vivek faced, however, was that most African maize varieties are white, and most Asian maize varieties are yellow. “You cannot directly deploy what you breed in Africa into Asia,” Vivek says. “Plus, there’s so much difference in the environments [between Africa and Asia] and maize is very responsive to its environment.”

The advances in marker-assisted breeding since the inception of GCP contributed significantly towards the success of Vivek’s team.

“In collaboration with GCP, IITA, Cornell University and Monsanto, CIMMYT has initiated the largest public sector MARS breeding approach in the world,” says Vivek.

The outcome is good: “We now have some early-generation, yellow, drought-tolerant inbred germplasm and lines suitable for Asia.

“GCP gave us a good start. We now need to expand and build on this,” says Vivek.

GCP’s supported work laid the foundation for other CIMMYT projects, such as the Affordable, Accessible, Asian Drought-Tolerant Maize project funded by the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture. This project is developing yet more germplasm with drought tolerance.

A better picture: GCP brightens maize research

Dickson Ligeyo’s worries of a stormy future for Kenya’s maize production have lifted over the 10 years of GCP. At the end of 2014, Kenya had two new varieties that were in the final stage of testing in the national performance trials before being released to farmers.

“There is a brighter picture for Kenya’s maize production since we have acquired acid-tolerant germplasm from Brazil, which we are using in our breeding programmes,” Dickson says.

In West Africa, researchers are also revelling in the opportunity they have been given to help enhance local yields in the face of a changing climate. “My institute benefited from GCP not only in terms of human resource development, but also in provision of some basic equipment for field phenotyping and some laboratory equipment,” says Allen Oppong in Ghana.

“Through the support of GCP, I was able to characterise maize landraces found in Ghana using the bulk fingerprinting technique. This work has been published and I think it’s useful information for maize breeding in Ghana – and possibly other parts of the world.”

The main challenge now for breeders, according to Allen, is getting the new varieties out to farmers: “Most people don’t like change. The new varieties are higher yielding, disease resistant, nutritious – all good qualities. But the challenge is demonstrating to farmers that these materials are better than what they have.”

This Kenyan farmer is very happy with his healthy maize crop, grown using an improved variety during a period of drought.

Certainly GCP has strengthened the capacity of researchers across Africa, Asia and Latin America, training researchers in maize breeding, data management, statistics, trial evaluations and phenotyping. The training has been geared so that scientists in developed countries can use genetic diversity and advanced plant science to improve crops for greater food security in the developing world.

Elliot Tembo, a maize breeder with the private sector in sub-Saharan Africa says: “As a breeder and a student, I have been exposed to new breeding tools through GCP. Before my involvement, I was literally blind in the use of molecular tools. Now, I am no longer relying only on pedigree data – which is not always reliable – to classify germplasm.”

Allen agrees: “GCP has had tremendous impact on my life as a researcher. The capacity-building programme supported my training in marker-assisted selection training at CIMMYT in Mexico. This training exposed me to modern techniques in plant breeding and genomics. Similarly, it built my confidence and work efficiency.”

There is no doubt that GCP research has brightened the picture for maize research and development where it is most needed: with researchers in developing countries where poor farmers and communities rely on maize as their staple food and main crop.

More links

- Here on the Sunset Blog: comparative genomics | partnership with EMBRAPA | Sam’s story

- Blogposts on the GCP Blog: maize | comparative genomics

- Maize presentations (on SlideShare)

- Maize Research Initiative | InfoCentre

- Comparative Genomics Research Initiative | InfoCentre

- Maize Community of Practice (on IBP website)