Where to begin a decade-long story like that of the CGIAR Generation Challenge Programme (GCP)? This time-bound programme concluded in 2014 after successfully catalysing the use of advanced plant breeding techniques in the developing world.

Where to begin a decade-long story like that of the CGIAR Generation Challenge Programme (GCP)? This time-bound programme concluded in 2014 after successfully catalysing the use of advanced plant breeding techniques in the developing world.

Like all good tales, the GCP story had a strong theme: building partnerships in modern crop breeding for food security. It had a strong cast of characters: a palpable community of staff, consultants and partners from all over the world. And it had a formidable structure – two distinct phases split equally over the decade to first discover new plant genetic information and tools, and then to apply what the researchers learnt to breed more tolerant and resilient crops.

In October 2014, at the final General Research Meeting in Thailand, GCP Director Jean-Marcel Ribaut paid tribute to GCP’s cast and crew: “To all the people involved in GCP over the last 12 years, you are the real asset of the Programme,” he told them.

“In essence, our work has been all about partnerships and networking, bringing together players in crop research who may otherwise never have worked together,” says Jean-Marcel. “GCP’s impact is not easy to evaluate but it’s extremely important for effective research into the future. We demonstrated proofs of concept that can be scaled up for powerful results.”

A significant aspect of GCP’s legacy is the abundance of collaborations it forged and fostered between international researchers. A typical GCP project brought together public and private partners from both developing and developed nations and from CGIAR Centres. In all, more than 200 partners collaborated on GCP projects.

Just some of the extended GCP family assembled for the Programme’s final General Research Meeting in 2014.

The idea that the ‘community would pave the way towards success’ was always a key foundation of GCP, according to Dave Hoisington, who was involved with GCP from its conception and was latterly Chair of GCP’s Consortium Committee. “We designed GCP to provide opportunities for researchers to work together,” says Dave. He is a senior research scientist and program director at the University of Georgia, and was formerly Director of Research at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) and Director of the Genetic Resources Program and of the Applied Biotechnology Center at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

“GCP was the mechanism that would help us to complete our mission – to tap into the rich genetic diversity of crops and package it so that breeding programme researchers could integrate it into their operations,” says Dave.

The dawn of a new generation

Food security in the developing world continues to be one of the greatest global challenges of our time. One in nine people worldwide – or more than 820 million people – go hungry every day.

Although this figure is currently diminishing, a changing global climate is making food production more challenging for farmers. Farmers need higher yielding crops that can grow with less water, tolerate higher temperatures and poorer soils, and resist pests and diseases.

The turn of the millennium saw rapid technological developments emerging in international molecular plant science. New tools and approaches were developed that enabled plant scientists, particularly in the developing world, to make use of genetic diversity in plants that was previously largely inaccessible to them. These tools had the potential to increase plant breeders’ capacity to rapidly develop crop varieties able to tolerate extreme environments and yield more in farmers’ fields.

Dave was one scientist who early on recognised the significance and potential of this new dawn in plant science. In 2002, while working at CIMMYT, he teamed up with the Center’s then Director General, Masa Iwanaga, and its then Executive Officer for Research, Peter Ninnes – another long-term member of the GCP family who at the other end of the Programme’s lifespan became its Transition Manager. Together with a Task Force of other collaborators from CIMMYT, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and IPGRI (now Bioversity International), they drafted and presented a joint proposal to form a CGIAR Challenge Programme – and so GCP was conceived.

The five CGIAR Challenge Programmes were the early precursors of the current CGIAR Research Programs. They introduced a new model for collaboration among CGIAR Research Centers and with external institutes, particularly national breeding programmes in developing countries.

A programme where the spirit is palpable

Failed harvest: this Ghanaian farmer’s maize ears are undersized and poorly developed due to drought.

From the beginning, GCP had collaboration and capacity building at its heart. As encapsulated in its tagline, “partnerships in modern crop breeding for food security,” GCP’s aim was to bring breeders together and give them the tools to more effectively breed crops for the benefit of the resource-poor farmers and their families, particularly in marginal environments.

GCP’s primary focus on was on drought tolerance and breeding for drought-prone farming systems, since this is the biggest threat to food security worldwide – and droughts are already becoming more frequent and severe with climate change. However, the Programme made major advances in breeding for resilience to other major stresses in a number of different crops, including acid soils and important pests and diseases. It also sought improved yields and nutritional quality.

The model for the Programme was that it would work by contracting partner institutes to conduct research, initially through competitive projects and later through commissioning. These partnerships would ensure that GCP’s overall objectives were met. For Dave, GCP set the groundwork for modern plant breeding.

“GCP demonstrated that you can tap into genetic resources and that they can be valuable and can have significant impacts on breeding programmes,” he says.

“I think GCP started to guide the process. Without GCP, the adoption, testing and use of molecular technologies would probably have been delayed.”

Masa Iwanaga, who is now President of the Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences (JIRCAS), says that the key to the proposal and ultimate success of GCP was the focus on building connections between partners worldwide. “By providing the opportunity for researchers from developed countries to partner with researchers in developing countries, it helped enhance the capacity of national programmes in developing countries to use advanced technology for crop improvement.”

While not all partnerships were fruitful, Jean-Marcel has observed that those participants who invested in partnerships and built trust, understanding and communication produced some of the most successful results. “We created this amazing chain of people, stretching from the labs to the fields,” said Jean-Marcel, discussing the Programme in a 2012 interview.

“Perhaps the best way I can describe it is as a ‘GCP spirit’ created by the researchers we worked with.

“The Programme’s environment is friendly, open to sharing and is marked by a strong sense of community and belonging. The GCP spirit is visible and palpable: you can recognise people working with us have a spirit that is typical of the Programme.”

Exploring gene banks to uncover genetic wealth

GCP started operations in 2004 and was designed in two five-year phases, 2004–2008 and 2009–2013. 2014 was a transition year for orderly closure.

Phase I focussed on upstream research to generate knowledge and tools for modern plant breeding. It mainly consisted of exploration and discovery projects, funded on a competitive basis, pursuing the most promising molecular research and high-potential partnerships.

“GCP’s first task was to go in and identify the genetic wealth held within the CGIAR gene banks,” says Dave Hoisington.

CGIAR’s gene banks were originally conceived purely for conservation, but breeders increasingly recognised the tremendous value of studying and utilising these collections. Over the years they were able to use gene banks as a valuable source of new breeding material, but were hampered by having to choose seeds almost blindly, with limited knowledge of what useful traits they might contain.

“We realised we could use molecular tools to help scan the genomes and discover genes in crops of interest and related species,” says Dave. “The genes we were most interested in were ones that helped increase yield in harsh environments, particularly under drought.”

By studying the genomes of wild varieties of wheat, for example, researchers found genes that increase wheat’s tolerance of water stress.

GCP-supported projects analysed naturally occurring genetic diversity to produce cloned genes, informative markers and reference sets for 21 important food crops. ‘Reference sets’, or ‘reference collections’ reduce search time for researchers: they are representative selections of a few hundred plant samples (‘accessions’) that encapsulate each crop’s genetic diversity, narrowed down from the many thousands of gene bank accessions available. The resources developed through GCP have already proved enormously valuable, and will continue to benefit researchers for years to come.

For example, researchers developed 52 new molecular (DNA) markers for sweetpotato to enable marker-assisted selection for resistance to sweet potato virus disease (SPVD). For lentils, a reference set of about 150 accessions was produced, a distillation down to 15 percent of the global collection studied. And for barley, 90 percent of all the different characteristics of barley were captured within 300 representative plant lines.

The leader of GCP’s barley research, Michael Baum, who directs the Biodiversity and Integrated Gene Management Program at the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), says the reference set is a particular boon for a researcher new to barley.

“By looking at 300 lines, they see the diversity of 3,000 lines without any duplication,” says Michael. “This is much better and quicker for a plant breeder.”

Similarly, the lentil reference set serves as a common resource for ICARDA’s team of lentil breeders, facilitating efficient collaboration, according to Aladdin Hamweih of ICARDA, who was charged with developing the lentil collection for GCP.

“These materials can be accessed to achieve farming goals – to produce tough plants suitable for local environments. In doing this, we give farmers a greater likelihood of success, which ultimately leads to improving food security for the wider population,” Aladdin says.

An important aspect of the efforts within Phase I was GCP’s emphasis on developing genomic resources such as reference sets for historically under-resourced crops that had received relatively little investment in genetic research. These made up most of GCP’s target crops, and included: bananas and plantains; cassava; coconuts; common beans; cowpeas; chickpeas; groundnuts; lentils; finger, foxtail and pearl millets; pigeonpeas; potatoes; sorghum; sweetpotatoes and yams.

Although not all of these historically under-resourced crops continued to receive research funding into Phase II, the outcomes from Phase I provided valuable genetic resources and a solid basis for the ongoing use of modern, molecular-breeding techniques. Indeed, thanks to their GCP boost, some of these previously neglected species have become model crops for genetic and genomic research – even overtaking superstar crops such as wheat, whose highly complex genome hampers scientists’ progress.

A need to focus and deliver products

“Phase I provided plenty of opportunity for researchers to tap into genetic diversity,” says Jean-Marcel. “We opened the door for a lot of different topics which helped us to identify projects worth pursuing further, as well as identifying productive partnerships. But at the same time, we were losing focus by spreading ourselves too thinly across so many crops.”

This notion was confirmed by the authors of an external review conducted in 2008, commissioned by CGIAR. This recommended consolidating GCP’s research in order to optimise efficiency and increase outputs during GCP’s second phase, while also enhancing potential for longer term impact.

Transparency and a willingness to respond and adapt were always core GCP values. The Programme embraced external review throughout its lifetime, and was able to make dynamic changes in direction as the best ways to achieve impact emerged. Markus Palenberg, Managing Director of the Institute for Development Strategy in Germany, was a member of the 2008 evaluation panel.

“One major recommendation from the evaluation was to focus on crops and tools which would provide the greatest impact in terms of food security,” recounts Markus, who later joined GCP’s Executive Board. “This resulted in the Programme refocusing its research on only nine core crops.” These were cassava, beans, chickpeas, cowpeas, groundnuts, maize, rice, sorghum and wheat.

GCP’s decision-making process on how to focus its Phase II efforts was partly guided by research the Programme had commissioned, documented in its Pathways to impact brief No 1: Where in the world do we start? This took global data on the number of stunted – i.e., severely malnourished – children, as a truer indicator of poverty than a monetary definition, and overlaid it on maps showing where drought was most likely to occur and have a serious impact on crop productivity. This combination of poverty and vulnerable harvests was used to determine the farming systems where GCP might have most impact.

The Programme also attempted to maintain a balance between types of crops, including each of the following categories: cereals (maize, rice, sorghum, wheat), legumes (beans, chickpeas, cowpeas, groundnuts), and roots and tubers (cassava).

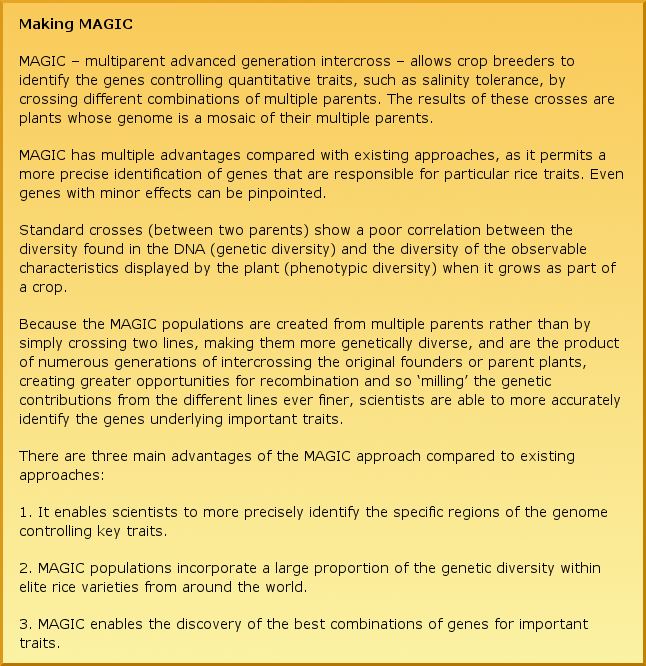

The crops were organised into six crop- specific Research Initiatives (RIs) – legumes were consolidated into one – plus a seventh, Comparative Genomics, which focused on exploiting genetic similarities among rice, maize and sorghum to find and deploy sources of tolerance to acid soils.

The research under the RIs built on GCP’s achievements in Phase I, moving from exploration to application. The change in focus was underpinned by the planned shift from competitive to commissioned projects, allowing the Programme to continue to support its strongest partnerships and research strands.

“The RIs focused on promoting the use of modern integrated breeding approaches, using both conventional and molecular breeding methods, to improve each crop through a series of specific projects undertaken in more than 30 countries,” says Jean-Marcel. “More importantly, the RIs were focused on creating new genetic material and varieties of plants that would ultimately benefit farmers.”

Such products released on the ground included new varieties of:

- cassava resistant to several diseases, tolerant to drought, nutritionally enhanced to provide high levels of vitamin A, and with higher starch content for high-quality cassava flour and starch processing

- chickpea tolerant to drought and able to thrive in semi-arid conditions, already providing improved food and income security for smallholder African farmers – yields have doubled in Ethiopia – and set to help them supply growing demand for the legume in India

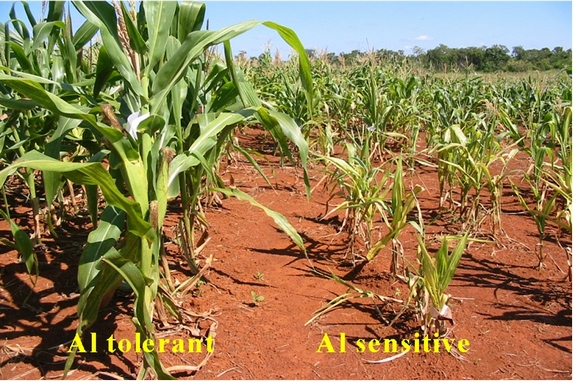

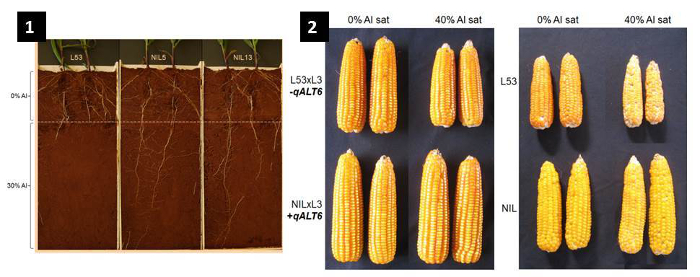

- maize with higher yields, tolerant to high levels of aluminium in acid soils, resistant to disease, adapted to local conditions in Africa – and with improved phosphorus efficiency in the pipeline

- rice with tolerance to drought and low levels of phosphorus in acid soils, disease resistance, high grain quality, and tolerance to soil salinity – with improved aluminium tolerance on the way too

Over the coming years, many more varieties developed through GCP projects are expected to be available to farmers, as CGIAR Research Centres and national programmes continue their work.

These will include varieties of:

- common bean resistant to disease and tolerant to drought and heat, with higher yields in drier conditions – due for release in several African countries from 2015 onwards

- cowpea resistant to diseases and insect pests, with higher yields, and able to tolerate worsening drought – set for release in several countries from 2015, to secure and improve harvests in sub-Saharan Africa

- groundnut tolerant to drought and resistant to pests, diseases, and the fungi that cause aflatoxin contamination, securing harvests and raising incomes in some of the poorest regions of Africa

- maize tolerant to drought and adapted to local conditions and tastes in Asia

- sorghum that is even more robust and adapted to increasing drought in the arid areas of sub-Saharan Africa – plus sorghum varieties able to tolerate high aluminium levels in acid soils, set for imminent release

- wheat with heat and drought tolerance – as well as improved yield and grain quality – for India and China, the two largest wheat producers in the world

Giving a voice to all the cast and crew

The 2008 external review also recommended slight changes in governance. It suggested GCP receive more guidance from two proposed panels: a Consortium Committee and an independent Executive Board.

Dave Hoisington, who chaired the Committee from 2010, succeeding the inaugural Chair Yves Savidan, explains: “GCP was not a research programme run by a single institute, but a consortium of 18 institutes. By having a committee of the key players in research as well as an independent board comprising people who had no conflict of interest with the Programme, we were able to make sure both the ‘players’ and ‘referees’ were given a voice.”

Jean-Marcel says providing this voice to everyone involved was an important facet of effective management. “Given that GCP was built on its people and partnerships, it was important that we restructured our governance to provide everyone with a representative to voice their thoughts on the Programme. We have always tried to be very transparent.”

The seven-member Executive Board was instated in June 2008 to provide oversight of the scientific strategy of the Programme. Board members had a wide variety of skills and backgrounds, with expertise ranging across molecular biology, development assistance, socioeconomics, academia, finance, governance and change management.

Andrew Bennett, who followed inaugural Chair Calvin Qualset into the role in 2009, has more than 45 years of experience in international development and disaster management and has worked in development programmes in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Pacific and the Caribbean.

“The Executive Board’s first role was to provide advice and to help the Consortium Committee and management refocus the Programme,” says Andrew.

‘Advice’ and ‘helping’ are not usually words associated with how a Board works but, like so much of GCP’s ‘family’, this was not a typical board. Because GCP was hosted by CIMMYT, the Board did not have to deal with any policy issues; that was the responsibility of the Consortium Committee. As Andrew explains, “Our role was to advise on and help with decision-making and implementation, which was great as we were able to focus on the Programme’s science and people.”

Andrew has been impressed by what GCP has been able to achieve in its relatively short lifespan in comparison with other research programmes. “I think this programme has demonstrated that a relatively modest amount of money used intelligently can move with the times and help identify areas of potential benefit.”

Developing capacity and leadership in Africa

As GCP’s focus shifted from exploration and discovery to application and impact between Phases I and II, project leadership shifted too. More and more projects were being led by developing-country partners.

Harold Roy-Macauley, GCP Board member and Executive Director of the West and Central African Council for Agricultural Research and Development (WECARD), advised GCP about how to develop capacity, community and leadership among African partners so that products would reach farmers.

“The objective was to make sure that we were influencing development within local research communities,” says Harold. “GCP has played a very important role in creating synergies between the different institutions in Africa. Bringing the right people together, who are working on similar problems, and providing them with the opportunity to lead, has brought about change in the way researchers are doing research.”

In the early years of the Programme, only about 25 percent of the research budget was allocated to research institutes in developing countries; this figure was more than 50 percent in 2012 and 2013.

Jean-Marcel echoes Harold’s comments: “To make a difference in rural development – to truly contribute to improved food security through crop improvement and incomes for poor farmers – we knew that building capacity had to be a cornerstone of our strategy,” he says. Throughout its 10 years, GCP invested 15 percent of its resources in developing capacity.

“Providing this capacity has enabled people, research teams and institutes to grow, thrive and stand on their own, and this is deeply gratifying. It is very rewarding to see people from developing countries growing and becoming leaders,” says Jean-Marcel.

“For me, seeing developing-country partners come to the fore and take the reins of project leadership was one of the major outcomes of the Programme. Providing them with the opportunity, along with the appropriate capacity, allowed them to build their self-confidence. Now, many have become leaders of other transnational projects.”

Emmanuel Okogbenin and Chiedozie Egesi, two plant breeders at Nigeria’s National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI), are notable examples. They are leading an innovative new project using marker-assisted breeding techniques they learnt during GCP projects to develop higher-yielding, stress-tolerant cassava varieties. For this project, they are partnering with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Cornell University in the USA, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and Uganda’s National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI).

Chiedozie says this would not have been possible without GCP helping African researchers to build their profiles. “GCP helped us to build an image for ourselves in Nigeria and in Africa,” he says, “and this created a confidence in other global actors, who, on seeing our ability to deliver results, are choosing to invest in us.”

A ‘sweet and sour’ sunset

Jean-Marcel defined GCP’s final General Research Meeting in Thailand in 2014 as a ‘sweet-and-sour experience’.

Summing up the meeting, Jean-Marcel said, “It was sour in terms of GCP’s sunset, and sweet in terms of seeing you all here, sharing your stories and continuing your conversations with your partners and communities.”

From the outset, GCP was set up as a time-bound programme, which gave partners specific time limits and goals, and the motivation to deliver products. However, much of the research begun during GCP projects will take longer than 10 years to come to full fruition, so it was important for GCP to ensure that the research effort could be sustained and would continue to deliver farmer-focused outcomes.

During the final two years of the Programme, the Executive Board, Consortium Committee and Management Team played a large role in ensuring this sustainability through a thoroughly planned handover.

“We knew we weren’t going to be around forever, so we had a plan from early on to hand over the managerial reins to other institutes, including CGIAR Research Programs,” says Jean-Marcel.

One of the largest challenges was to ensure the continuity and future success of the Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP). IBP is a web-based, one-stop shop for information, tools and related services to support crop breeders in designing and carrying out integrated breeding projects, including both conventional and marker-assisted breeding methods.

While there are already a number of other analytical and data management breeding systems on the market, IBP combines all the tools that a breeder needs to carry out their day-to-day logistics, plan crosses and trials, manage and analyse data, and analyse and refine breeding decisions. IBP is also unique in that it is geared towards supporting breeders in developing countries – although it is already proving valuable to a wide range of breeding teams across the world. The Platform is set up to grow and improve as innovative ideas emerge, as users can develop and share their own tools.

Beyond the communities and relationships fostered by GCP community, Jean-Marcel sees IBP as the most important legacy of the Programme. “I think that the impact of IBP will be huge – so much larger than GCP. It will really have impact on how people do their business, and adopt best practice.”

While the sun is setting on GCP, it is rising for IBP, which is in an exciting phases as it grows and seeks long-term financial stability. The Platform is now independent, with its headquarters hosted at CIMMYT, and has established a number of regional hubs to provide localised support and training around the world, with more to follow.

It is envisaged that IBP will be invaluable to researchers in both developing and developed countries for many years to come, helping them to get farmers the crop varieties they need more efficiently. IBP is also helping to sustain some of the networks that GCP built and nurtured, as it is hosting the crop-specific Communities of Practice established by GCP.

2014 may be the end of GCP’s story but its legacy will live on. It will endure, of course, in the Programme’s scientific achievements – for many crops, genetic research and the effective use of genetic diversity in molecular breeding are just beginning, and GCP has helped to kick-start a long and productive scientific journey – and in the valuable tools brought together in IBP. And most of all, GCP’s character, communities and spirit will live on in all those who formed part of the GCP family.

For Chiedozie Egesi, the partnerships fostered by GCP have changed the way he does research: “We now have a network of cassava breeders that you can count on and relate with in different countries. This has really widened our horizons.

Fellow cassava breeder Elizabeth Parkes of Ghana agrees that GCP’s impact will be a lasting one: “All the agricultural research institutes and individual scientists who came into contact with GCP have been fundamentally transformed.”