Crop science and collaboration help African farmers feed India’s appetite for chickpeas

Indian chickpea farmer with her harvest.

India loves chickpeas. With its largely vegetarian population, it has long been the world’s biggest producer and consumer of the nutritious legume. In recent years, however, India’s appetite for chickpea has outstripped production, and the country is also now the world’s biggest importer. With a ready market and new drought-tolerant varieties of chickpea, millions of smallholder African farmers are ready to make up India’s shortfall, improving livelihoods along the way and ensuring food security for some of the world’s most resource-poor countries.

GCP achieved real impacts in chickpea by catalysing and facilitating the deployment of advanced crop science, particularly molecular breeding, in the development of drought-tolerant varieties for both Africa and Asia. Over the course of its research, it also contributed to major advances in chickpea science and genomic knowledge.

Although India boasts the world’s biggest total chickpea harvest, productivity has been low in recent years with yields of less than one tonne per hectare, largely due to drought in the south of the country where much chickpea is grown. The country is relying increasingly on exports from producers in sub-Saharan Africa to supplement its domestic supply.

Drought has been hindering chickpea yields in Africa too, however, and this is a major concern not only for Africa but also for India. Ethiopia and Kenya are Africa’s largest chickpea producers, and both countries have been producing chickpea for export. However, their productivity has been limited, mainly because of heat stress and moisture loss, as well as by a lack of access to basic infrastructure and resources.

Indeed, drought has been the main constraint to chickpea productivity worldwide, and in countries such as Ethiopia and Kenya this is often made worse by crop disease, poor soil quality and limited farmer resources. While total global production of chickpea is around 8.6 million tonnes per year, drought causes losses of around 3.7 million tonnes worldwide.

A decade ago, chickpea researchers, supported by the CGIAR Generation Challenge Programme (GCP), started to consider the potential for developing new drought-tolerant varieties that could help boost the world’s production.

They posed this question: If struggling African farmers were armed with adequate resources, could they make up India’s shortfall by growing improved chickpea varieties for export? Empowering farmers to stimulate and sustain their own food production, it was proposed, would not only offer food security to millions of farmers, but could ultimately secure future chickpea exports to India.

An Ethiopian farmer harvests her chickpea crop.

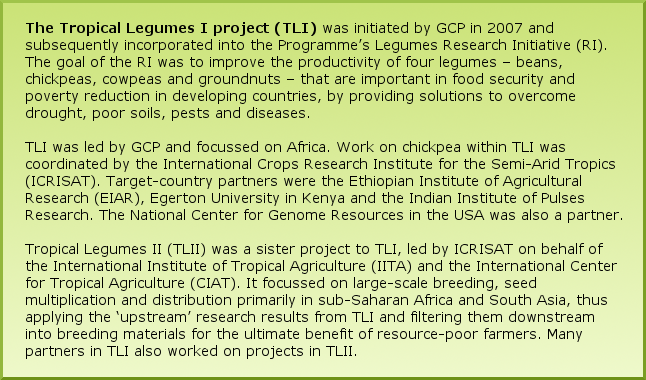

In 2007, GCP kicked off a plan for a multiphased, multithemed Tropical Legumes I (TLI) project, which later became part of, and the largest project within, the GCP Legumes Research Initiative (RI; see box below) – the chickpea component of which would involve collaboration between researchers from India, Ethiopia and Kenya. The scope was not only to develop improved, drought-tolerant chickpeas that would thrive in semiarid conditions, but also to ensure that these varieties would be growing in farmers’ fields across Africa and South Asia within a decade.

“We knew our task would not be complete until we had improved varieties in the hands of farmers,” says GCP researcher Paul Kimurto from the Faculty of Agriculture, Egerton University, Kenya.

The success of GCP research in achieving these goals has opened up great opportunities for East African countries such as Ethiopia and Kenya, which are primed and ready to take advantage of a guaranteed chickpea market.

How drought affects chickpea

Chickpea is a pretty tough customer overall, being able to withstand and thrive on the most rugged and dry terrains, surviving with no irrigation – only the moisture left deep in the soil at the end of the rainy season.

Yet the legume does have one chink in its armour: if no rain falls at its critical maturing or ripening stage (otherwise known as the grain-filling period), crop yields will be seriously affected. The size and weight of chickpea legumes is determined by how successful this maturing stage is. Any stress, such as drought or disease, that occurs at this time will reduce the crop’s yield dramatically.

In India, this has been a particular problem for the past 40 years or so, as chickpea cropping areas have shifted from the cooler north to the warmer south.

“In the 1960s and 1970s when the agricultural Green Revolution introduced grain crops to northern India, chickpeas began to be replaced there by wheat or rice, and grown more in the south,” says Pooran Gaur from the International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), headquartered in India. Pooran was an Activity Leader for the first phase of TLI and Product Delivery Coordinator for the chickpea component of the Legumes RI.

This shift meant the crop was no longer being grown in cooler, long-season environments, but in warmer, short-season environments where drought and diseases like Fusarium wilt have inhibited productivity.

“We have lost about four or five million hectares of chickpea growing area in northern India in the decades since that time,” says Pooran. “In the central and southern states, however, chickpea area more than doubled to nearly five million hectares.”

Escaping drought in India

“The solution we came up with was to develop varieties that were not only high yielding, but could also mature earlier and therefore have more chance of escaping terminal drought,” Pooran explains.

“Such varieties could also allow cereal farmers to produce a fast-growing crop in between the harvest and planting of their main higher yielding crops,” he says.

New short-duration varieties are expected to play a key role in expanding chickpea area into new niches where the available crop-growing seasons are shorter.

“In southern India now we are already seeing these varieties growing well, and their yield is very high,” says Pooran. “In fact, productivity has increased in the south by about seven to eight times in the last 10–12 years.”

The southern state of Andhra Pradesh, once considered unfavourable for chickpea cultivation, today has the highest chickpea yields (averaging 1.4 tonnes/hectare) in India, producing almost as much chickpea as Australia, Canada, Mexico and Myanmar combined.

Indian chickpea farmer with her harvest.

Developing new varieties: Tropical Legumes I in action

GCP-supported drought-tolerance breeding activities in chickpea created hugely valuable breeding materials and tools during the Programme’s decade of existence, focussing not only in India but African partner countries of Ethiopia and Kenya too. A key first step in Phase I of TLI was to create and phenotype – i.e. measure and record the observable characteristics of – a chickpea reference set. This provided the raw information on physical traits needed to make connections between phenotype and genotype, and allowed breeders to identify materials likely to contain drought tolerance genes. This enabled the creation in Phase II of breeding populations with superior genotypes, and so the development of new drought-tolerant prebreeding lines to feed into TLII.

A significant number of markers and other genomic resources were identified and made available during this time, including simple sequence repeats (SSRs), single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and Diversity Array Technologies (DArT) arrays. The combination of genetic maps with phenotypic information led to the identification of an important ‘hot spot’ region containing quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for several drought-related traits.

Two of the most important molecular-breeding approaches, marker-assisted backcrossing (MABC) and marker-assisted recurrent selection (MARS), were then employed extensively in the selection of breeding materials and introgression of these drought-tolerance QTLs and other desired traits into elite chickpea varieties.

Developing chickpea pods

Markers – DNA sequences with known locations on a chromosome – are like flags on the genetic code. Using them in molecular breeding involves several steps. Scientists must first discover a large number of markers, of which only a small number are likely to be polymorphic, i.e. to have different variants. These are then mapped and compared with phenotypic information, in the hope that just one or two might be associated with a useful trait. When this is the case, breeders can test large quantities of breeding materials to find out which have genes for, say, drought tolerance without having to grow plants to maturity.

The implementation of techniques such as MABC and MARS has become ever more effective over the course of GCP’s work in chickpea, thanks to the emergence and development of increasingly cost-effective types of markers such as SNPs, which can be discovered and explored in large numbers relatively cheaply. The integration of SNPs into chickpea genetic maps significantly accelerated molecular breeding.

The outcome of all these molecular-breeding efforts has been the development and release of locally adapted, drought-tolerant chickpea varieties in each of the target countries – Ethiopia, Kenya and India – where they are already changing lives with their significantly higher yields. Further varieties are in the pipeline and due for imminent release, and it is anticipated that, with partner organisations adopting the use of molecular markers as a routine part of their breeding programmes, many more will be developed over the coming years.

Molecular breeding in TLI was done in conjunction with target-country partners, with at least one cross carried out in each country. ICRISAT also backed up MABC activities with additional crosses. The elite lines that were developed underwent multilocation phenotyping in the three target countries and the best-adapted, most drought-tolerant lines were promoted in TLII.

The project placed heavy emphasis on capacity building for the target-country partners. Efforts were made, for instance, to help researchers and breeders at Egerton University in Kenya and the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR) in Ethiopia to undertake molecular breeding activities. At least one PhD and two Master’s students each from Kenya, Ethiopia and India were supported throughout this capacity-building process.

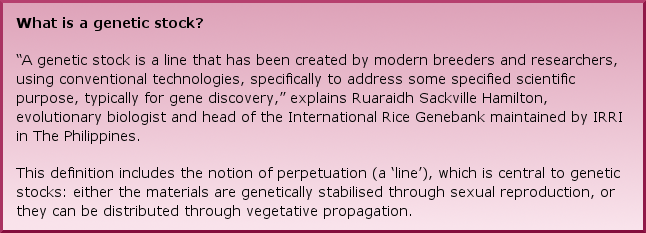

The magic of genetic diversity

One of the important advances in chickpea science supported by GCP, as part of TLI and its mission to develop drought-tolerant chickpea genotypes, was the development of the first ever chickpea multiparent advanced generation intercross (MAGIC) population.

It was created using eight well-adapted and drought-tolerant desi chickpea cultivars and elite lines from different genetic origins and backgrounds, including material from Ethiopia, Kenya, India and Tanzania. These were drawn from the chickpea reference set that GCP had previously developed and phenotyped, allowing an effective strategic selection of parental lines. The population was created by crossing these over several generations in such a way as to maximise the mix of genes in the offspring and ensure varied combinations.

MAGIC populations like these are a valuable genetic resource that makes trait mapping and gene discovery much easier, helping scientists identify useful genes and create varieties with enhanced genetic diversity. They can also be directly used as source material in breeding programmes; already, phenotyping a subset of the chickpea MAGIC population has led to the identification of valuable chickpea breeding lines that had favourable alleles for drought tolerance.

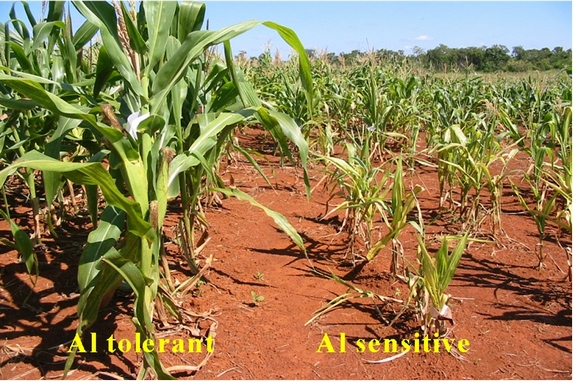

Through links with future molecular-breeding projects, it is expected that the investment in the development of MAGIC populations will benefit both African and South Asian chickpea production. GCP was also involved in developing MAGIC populations for cowpea, rice and sorghum, which were used to combine elite alleles for both simple traits, such as aluminium tolerance in sorghum and submergence tolerance in rice, and complex traits, such as drought or heat tolerance.

Decoding the chickpea genome

Chickpea seed

In 2013, GCP scientists, working with other research organisations around the world, announced the successful sequencing of the chickpea genome. This major breakthrough is expected to lead to the development of even more superior varieties that will transform chickpea production in semiarid environments.

A collaboration of 20 international research organisations under the banner of the International Chickpea Genome Sequencing Consortium (ICGSC), led by ICRISAT, identified more than 28,000 genes and several million genetic markers. These are expected to illuminate important genetic traits that may enhance new varieties.

“The value of this new resource for chickpea improvement cannot be overstated,” says Doug Cook from the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), United States. “It will provide the basis for a wide range of studies, from accelerated breeding, to identifying the molecular basis of a range of key agronomic traits, to basic studies of chickpea biology.”

Doug was one of three lead authors on the publication of the chickpea genome, along with Rajeev Varshney of ICRISAT, who was Principal Investigator for the chickpea work in GCP’s Legumes RI, and Jun Wang, Director of the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) of China.

“Making the chickpea genome available to the global research community is an important milestone in bringing chickpea improvement into the 21st century, to address the nutritional security of the poor – especially the rural poor in South Asia and Africa,” he says.

Increased food security will mean higher incomes and a better standard of living for farmers across sub-Saharan Africa.

For Pooran Gaur, GCP played the role of catalyst in this revolution in genomic resource development. “GCP got things started; it set the foundation. Now we are in a position to do further molecular breeding in chickpea.”

The chickpea genome-sequencing project was partly funded by GCP. Other collaborators included UC Davis and BGI-Shenzhen, with key involvement of national partners in India, Canada, Spain, Australia, Germany and the Czech Republic.

In September 2014, ICRISAT received a grant from the Indian Government for a three-year project to further develop chickpea genomic resources, by utilising the genome-sequence information to improve chickpea.

Indian women roast fresh green chickpeas for an evening snack in Andhra Pradesh, India.

Chickpea success in Africa: new varieties already changing lives

With high-yielding, drought tolerant chickpea varieties emerging from the research efforts in molecular breeding, GCP’s partners also needed to reach out to farmers. Teaching African farmers about the advantages of growing chickpeas, either as a main crop or a rotation crop between cereals, has brought about a great uptake in chickpea production in recent years.

A key focus during the second phase of TLI, and onward into TLII, was on enhancing the knowledge, skills and resources of local breeders who have direct links to farmers, especially in Ethiopia and Kenya, and so also build the capacity of farmers themselves.

“We’ve held open days where farmers can interact with and learn from breeders,” says Asnake Fikre, Crop Research Director for EIAR and former TLI country coordinator of the chickpea work in Ethiopia.

“Farmers are now enrolled in farmer training schools at agricultural training centres, and there are also farmer participatory trials.

“This has given them the opportunity to participate in varietal selection with breeders, share their own knowledge and have their say in which varieties they prefer and know will give better harvest, in the conditions they know best.”

EIAR has also been helping train farmers to improve their farm practices to boost production and to become seed producers of these high-yielding chickpea varieties.

“Our goal was to have varieties that would go to farmers’ fields and make a clearly discernible difference,” says Asnake. “Now we are starting to make that kind of impact in my country.”

In fields across Ethiopia, the introduction of new, drought-tolerant varieties has already brought a dramatic increase in productivity, with yields doubling in recent years. This has transformed Ethiopia’s chickpea from simple subsistence crop to one of great commercial significance.

“Targeted farmers are now planting up to half their land with chickpea,” Asnake says. “This has not only improved the fertility of their soil but has had direct benefits for their income and diets.”

Varieties like the large-seeded and high-valued kabuli have presented new opportunities for farmers to earn extra income through the export industry, and indeed chickpea exports from eastern Africa have substantially increased since 2001.

“The high yields of the drought-tolerant and pest-resistant chickpea, and the market value, meant that I am no longer seen as a poor widow but a successful farmer,” says Ethiopian farmer Temegnush Dabi.

“Ultimately, by making wealth out of chickpea and chickpea technologies in this country, people are starting to change their lives,” says Asnake. “They are educating their children to the university level and constructing better houses, even in towns. This will have a massive impact on the next generation.”

A similar success story is unfolding in Kenya, where GCP efforts during TLI led to the release of six new varieties of chickpea in the five years prior to GCP’s close at the end of 2014; more are expected to be ready within the next three years.

While chickpea is a relatively new crop in Kenya it has been steadily gaining popularity, especially in the drylands, which make up over 80 percent of Kenya’s total land surface and support nearly 10 million Kenyans – about 34 percent of the country’s population.

Drought tolerance experiments in chickpea at Egerton University, Njoro, Kenya.

“It wasn’t until my university went into close collaboration with ICRISAT during TLII and gained more resources and training options – facilitated by GCP – that chickpea research gained leverage in Kenya,” Paul Kimurto explains. “Through GCP and ICRISAT, we had more opportunities to promote the crop in Kenya. It is still on a small scale here, but it is spreading into more and more areas.”

Kenyan farmers are now discovering the benefits of chickpea as a rotational or ‘relay’ crop, he says, due to its ability to enhance soil fertility. In the highlands where fields are normally left dry and nothing is planted from around November to February, chickpea is a very good option to plant instead of letting fields stay fallow until the next season.

“By fixing nitrogen and adding organic matter to the soil, chickpeas can minimise, even eliminate, the need for costly fertilisers,” says Paul. “This is certainly enough incentive for cereal farmers to switch to pulse crops such as chickpea that can be managed without such costs.”

Households in the drylands have often been faced with hunger due to frequent crop failure of main staples, such as maize and beans, on account of climate change, Paul explains. With access to improved varieties, however, farmers can now produce a fast-growing chickpea crop between the harvest and planting of their main cereals. In the drylands they are now growing chickpeas after wheat and maize harvests during the short rains, when the land would otherwise lie fallow.

“Already, improved chickpeas have increased the food security and nutritional status of more than 27,000 households across the Baringo, Koibatek, Kerio Valley and Bomet areas of Kenya,” Paul says.

It is a trend he hopes will continue right across sub-Saharan Africa in the years to come, attracting more and more resource-poor farmers to grow chickpea.

Chickpea’s promise meeting future challenges

Beyond the end of GCP and the funding it provided, chickpea researchers are hopeful they will be able to continue working directly with farmers in the field, to ensure that their interests and needs are being addressed.

“To sustain integrated breeding practices post-2014, GCP has established Communities of Practice (CoPs) that are discipline- and commodity-oriented,” says Ndeye Ndack Diop, GCP’s Capacity Building Leader and TLI Project Manager. “The ultimate goal of the CoPs is to provide a platform for community problem solving, idea generation and information sharing.”

Ndeye Ndack has been impressed with the way the chickpea community has embraced the CoP concept, noting that Pooran has played an important part in this and the TLI projects. “Pooran was able to bring developing-country partners outside of TLI into the CoP and have them work on TLI-related activities. Being part of the community means they have been able to source breeding material and learn from others. In so doing, we are seeing these partners in Kenya and Ethiopia develop their own germplasm.

“Furthermore, much of this new germplasm has been developed by Master’s and PhD students, which is great for the future of these breeding programmes.”

“GCP played a catalytic role in this regard,” explains Rajeev Varshney. “GCP provided a community environment in ways that very few other organisations can, and in ways that made the best use of resources,” he says. “It brought together people from all kinds of scientific disciplines: from genomics, bioinformatics, biology, molecular biology and so on. Such a pooling of complementary expertise and resources made great achievements possible.”

An Ethiopian farmer loads his bounteous chickpea harvest onto his donkey.

For Rajeev, the challenge facing chickpea research beyond GCP’s sunset is whether an adequate framework will be there to continue bringing this kind of community together.

“But that’s what we’re trying to do in the next phase of the Tropical Legumes Project (Tropical Legumes III, or TLIII), which kicks off in 2015,” explains Rajeev, who will be TLIII’s Principal Investigator. TLIII is to be led by ICRISAT.

“We will continue to work with the major partners as we did during GCP, which will involve, first of all, upscaling the activities we are doing now,” he says. “India currently has the capacity, the resources, to do this.”

Rajeev is hopeful that the relatively smaller national partners from Ethiopia and Kenya, and associated partners such as Egerton University, EIAR and maybe others, will have similar opportunities. “We hope they can also start working with their governments, or with agencies like USAID, and be successful at convincing them to fund these projects into the future, as GCP has been doing,” he says.

“The process is like a jigsaw puzzle: we have the borders done, and a good idea of what the picture is and where the rest of the pieces will fit,” he says.

Certainly for Paul Kimurto, the picture is clear for the future of chickpea breeding in Kenya.

“Improvements in chickpea resources cannot end now that new varieties have started entering farmers’ fields,” he says. “We’ve managed to develop a good, solid breeding programme here at Egerton University. The infrastructure is in place, the facilities are here – we are indeed equipped to maintain the life and legacy of GCP well beyond 2015.”

This can only be good news for lovers of the legume in India. With millions of smallholder farmers in Kenya and Ethiopia poised to exploit a ready market for new varieties that will change their families’ lives, chickpea’s potential for ensuring food security across the developing world seems more promising than ever.

More links