“We raised up a new crop of cassava breeders in Africa – people who were bold enough to take up a molecular-breeding project and pursue it with support from international partners.”

So says Chiedozie Egesi, talking about the value and impact of one aspect of the CGIAR Generation Challenge Programme’s (GCP) 10-year, USD 20 million investment in building the capacity of plant breeders and scientists in developing countries.

Chiedozie, an Assistant Director and head of the cassava breeding team at Nigeria’s National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI), says he and others have benefited from learning the latest skills and techniques of molecular plant breeding.

“Prior to my GCP work, I was more or less a plant breeder, and a conventional one at that. Whilst I’d been exposed to molecular tools during my early work on yam and other crops, I was not applying them in my work back then. Now I and many other plant breeders are using these tools to improve a wide range of crops.”

Chiedozie Egesi examines disease-resistant cassava on a National Root Crops Research Institute breeding plot at Umudike, Nigeria. GCP helped him to combine his traditional breeding skills with advanced molecular techniques.

Creating a core of scientists skilled in molecular plant breeding

The objective of GCP’s capacity-building efforts was to develop a cohort of scientists in developing-country research institutes who are trained and confident in the use of modern breeding tools and who can, in turn, act as champions for other scientists to adopt the techniques. Molecular-breeding techniques in particular have the potential to considerably slash the time taken to develop a new crop variety, often by more than half. This is crucial for poor smallholder farmers in Africa, Asia and Latin America, who are looking for crops that are more productive, better able to tolerate drought and which can resist the onslaught of diseases and pests.

Unfortunately, the adoption of molecular breeding in developing countries faces bottlenecks, including the shortage of well-trained personnel, inadequate high-throughput genotyping capacity, poor phenotyping infrastructure, and the lack of information systems or useful analysis tools. And this is where capacity building is so important.

GCP Director Jean-Marcel Ribaut says that building the capacity of plant breeders and scientists in developing countries is crucial in transferring scientific knowledge to those who need it the most.

“To make a difference in rural development, to truly contribute to improved food security through crop improvement and incomes for poor farmers, we knew that building capacity had to be a cornerstone in our strategy,” he says.

Jean-Marcel adds that originally the idea of capacity building was mostly a ‘proof of concept’ demonstrating the impact that this kind of investment could have within national agricultural research programmes. This took time and evolved as GCP shifted from Phase I (exploration and discovery of new genes, 2004–08) to Phase II (application and impact, centring on breeding and services to breeders, 2009–14).

Capacity building became a core part of GCP during its second phase, with three key strategies: training of students and scientists through postgraduate programmes and short courses, the development of key learning resources for such researchers, and the provision of infrastructure to support molecular-breeding activities in developing countries.

Md. Sazzadur Rahman, Senior Scientific Officer in the Plant Physiology Division of the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, twice received GCP grants to enable him build his capacity in using advanced breeding techniques in rice breeding for salt tolerance. Here he is shown in 2011 as an on-the-job trainee at the International Rice Research Institute, in which he was supported by GCP, as he compares the root growth of rice seedlings after two weeks of salinity stress. “I am always trying to use and disseminate what I learned through GCP’s support,” he says.

Capacity-building partnerships make research visible

Ndeye Ndack Diop uses words such as ‘visibility’, ‘credibility’ and ‘respect’ to describe her experiences as GCP’s Capacity Building Theme Leader and Tropical Legumes I (TLI) Project Manager.

Capacity building builds on the existing strengths of individuals, communities and organisations to reach their developmental goals by giving them the skills they need, supporting their leadership aspirations, and involving them in decision-making processes. Ndeye Ndack says such an approach requires partnerships between the developing countries’ agricultural research programmes, CGIAR Centres and other academic researchers.

“By collaborating on GCP projects, the national programmes in developing countries were able to raise the visibility of their research work not only at the regional level but at the international level,” she says.

A key feature of GCP’s capacity building was the crop-centred Communities of Practice – founded by GCP and now hosted by the Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP) – which facilitate ongoing interaction between plant breeders through peer-to-peer support and knowledge-sharing.

Ghanaian cassava plant breeder Elizabeth Parkes is an active member of the Cassava Community of Practice, which aims to facilitate and support the integration of marker-assisted selection into cassava breeding and so accelerate the production and dissemination of farmer-preferred cassava varieties that are resistant to pests and diseases and tolerant of stresses such as drought.

“With the Community of Practice you can call on other scientists; you share talk, you share ideas, you share joy. We share everything together,” Elizabeth enthuses. “GCP has had a huge impact on research in Ghana, especially for cassava, rice, maize and yam. All the agricultural research institutes and individual scientists who came into contact with GCP have been fundamentally transformed.”

Training the next generation of molecular plant breeders

GCP supported at least 101 students taking formal postgraduate courses. Of these, 34 PhD and 14 Master’s students were fully funded by GCP, and 40 PhD and 13 Master’s students were partially funded.

The intention was to prepare the next generation of plant breeders in developing countries, focusing on sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia. The work conducted by supported students was tied to specific GCP work initiatives, so students directly contributed to the Programme’s research work while learning new skills and producing new knowledge.

Honoré Kam, of Burkina Faso, selecting plants in the field in the field as a student. While working on his PhD at the University of KwaZulu Natal, he received a six-month fellowship from GCP to carry out one aspect of his PhD research project related to the characterisation of the Burkina Faso rice collection using microsatellite markers. This not only provided valuable knowledge of rice diversity, it helped to launch his career in research, and he now works for the Africa Rice Center (AfricaRice).

Karl Kunert, of the University of Pretoria in South Africa, says engaging scientists early in their careers is critical to Africa’s future. He was involved in GCP’s capacity-building efforts early on, when he ran a 10-day GCP workshop on plant genetic diversity and molecular marker-assisted breeding in 2005, training 14 participants from 10 African countries.

He says capacity building has to start at the undergraduate level and extend to supporting postdoctoral scientists to visit advanced laboratories to develop research and teaching skills.

“Active partnership between universities, national research programmes and farmers in Africa is very limited,” says Karl, “and with few good examples of functioning technology transfer systems, African scientists – particularly those just starting their careers – only see bits and pieces of the big picture and are thus not as effective as they could be.”

Practical, hands-on training in molecular breeding

GCP developed and ran many customised short courses especially designed for breeders, scientists and technicians from Africa and Asia who were directly involved in GCP-supported projects.

Cornell University (USA) researcher Theresa Fulton, originally a plant breeder who now works in science education, began working on some of the capacity-building aspects when GCP started, teaching short workshops and training courses and creating materials. She says the materials developed for these courses are useful for those who have completed the courses as well as for those who then go on to teach others.

Theresa says such students who become teachers are ‘champions’: people who “got right in there; they used it [the course materials and skills], they immediately started applying it to their own data and their own plant-breeding programme. They’re also enthusiastic and ask for help when they need it.”

She says champions create the enthusiasm for other people to learn about and be part of the capacity-building initiative.

One such researcher who is enthusiastically applying molecular-breeding techniques learnt through GCP is Yonggui Xiao, a molecular plant breeder at the Institute of Crop Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS).

“Working as part of this GCP project [within the Wheat Research Initiative] provided me with my first opportunity to practice using molecular-breeding techniques to improve the quality and yield of wheat under drought conditions,” says Yonggui. “We have so far successfully used several markers to produce an advanced variety, with higher yield and preferred qualities [taste, grain colour] under water stress, which will be released to farmers next year.”

Innovative long-term training in integrated plant breeding

GCP’s short, practical courses were consolidated in 2012 into a comprehensive three-year Integrated Breeding Multiyear Course (IB–MYC). Implemented through IBP, the course focused on modern molecular-breeding strategies and informatics technologies.

The IB–MYC training programme consisted of an annual two-week residential programme run over three years – a total of six weeks of intensive training workshops supported by learning and data-management resources available through the IBP website.

The course was aimed at scientists directly and indirectly involved in breeding projects associated with the nine crops covered by GCP’s seven research initiatives, as well as soybean.

At the end of the three years, trainees were expected to have high proficiency in conventional and molecular-breeding methodologies and IBP tools and services. They also learnt about data collection and management and statistics and how to use IBP’s Breeding Management System (BMS) to design and manage their activities.

IB–MYC trainees who had never carried out molecular-breeding activities were also offered the opportunity to initiate a small project during the course. This introduced the participants to key techniques and tools, such as genotyping and the use of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers, and allowed them to analyse their own data during the training.

GCP’s original goal was to train a total of 180 scientists, with a target of 60 from each of three regions: Eastern and Southern Africa, West and Central Africa, and South and Southeast Asia. After receiving a list of nominees, GCP selected candidates based on a survey sent to them for completion, with 170 then able to attend in the first year.

There was some unavoidable attrition in the number of participants over the three years of the course. Some moved on to new jobs, and others were unable to attend later sessions for reasons such as illness, scheduling conflicts with other commitments, or difficulty in obtaining visas or authorisation to attend. A handful failed their assignments. However, most of the participants stayed the distance – indeed, attrition rates were unusually low, with interest in the course remaining above expectations. A total of 129 participants from 26 countries attended in 2014, the final year, of whom 31 (24%) were women.

IB–MYC facilitators and trainers came from a range of institutions: GCP; Wageningen University and Research Centre, the Netherlands, and partners (Universidad de la República, Uruguay, and Makerere University, Uganda); Cornell University’s Genomic Diversity Facility; the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT); and the Africa Rice Center.

Theresa says many of the participants had data of their own, which they were encouraged to bring and upload into the system: “By their third and final year it was very hands-on. No more lecturing.”

Daniel Ambachew, then a bean breeder at the Southern Agricultural Research Institute in Ethiopia, was an IB–MYC participant and is a wholehearted convert to the BMS. “It is a really fantastic tool,” said Daniel in subsequent reflections. “During the course we learnt about the importance of recording clear and consistent phenotypic data, and IBP helps us to do this as well as store it in a database. It makes it easier to refer to and learn from the past. I’m now trying to pass on the knowledge I’ve learnt as well as create and implement a data-management policy for all plant breeders and technicians in our institute.”

Mounirou El-Hassimi Sow, a rice breeder from the Africa Rice Center in Benin, also champions the knowledge he gained through IB–MYC.

“When I started working on a GCP project, the aim was to implement a marker-assisted recurrent selection (MARS) programme,” says Mounirou.

“For such a project you need precision in your selection.”

“When we started, I did not have the tools [to implement MARS]. But through GCP, I had access to a tool that was user-friendly, and I was trained how to use that tool. Now I’m selecting [breeding material] with more precision – I’m not fishing anymore during my selections.”

Mounirou also makes a special observation that the programme was not just about learning and using new tools.

“As a newcomer in the research area, I think I was very lucky to be here at that moment when GCP – all the funding, the tools, the network – appeared,” he says.

“If I had been doing my research 20 years ago, I would not have this chance. Beyond the tools that I’ve learnt, that I’m now applying, I’ve met many people; I think this is more valuable than even the tools.

“I know the tools. I know how to use them. But at the end of the day I may face some challenges using the tools. Now I know whom to refer it to when I have these kinds of challenges.”

Theresa says there has been a growing enthusiasm for the course from year to year: “It’s been a pleasure for me to see people who were sceptics in the beginning change their minds.

“I can think of a couple of people in particular who asked, ‘Why should I use molecular markers? They’re expensive’,” she says. “Some of those people are now the most enthusiastic users of the system, so that’s been great!”

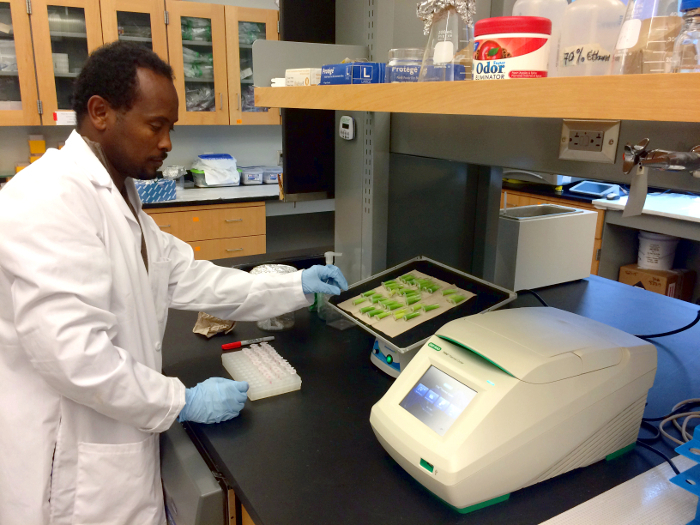

Daniel Ambachew, graduate of the Integrated Breeding Multiyear Course, has recently begun his PhD in Biotechnology at Tennessee State University in the USA, where he also works as a graduate research assistant in Matthew Blair’s plant genomics lab. Here he is shown preparing bean leaf sample for DNA extraction. He is currently on study leave from his home institute, Ethiopia’s Southern Agricultural Research Institute (SARI), where he is a Bean Breeder and Bean Improvement Program Leader, and he will be carrying out the field experiments for his doctoral studies at SARI. Meanwhile, he continues to be a committed BMS user and champion – he says that it has helped him a lot in his work, and he is now trying to introduce it in his new lab, where his colleagues are already interested, as well as at SARI.

Providing infrastructure and other support to breeders

It’s not enough to have the right skills in place; it’s also important that plant breeders have the resources and infrastructure they need to apply those skills. This may include irrigation systems, greenhouses, weather stations and electronic equipment such as tablets for field and laboratory data collection. Such resources mean that quality data can be collected, stored and accessed.

Capacity building must include infrastructure and maintenance to ensure the longevity and usefulness of people’s skills, according to GCP consultant Hannibal Muhtar, who has worked in the area of support services for most of his life. Hannibal was recruited by GCP to visit research sites of ongoing or potential GCP-funded projects across Africa and identify those where effective scientific research might be hampered by significant gaps in three fundamental areas: infrastructure, equipment and support services. He selected 19 research sites in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Tanzania.

Hannibal says the researcher is like a surgeon who needs to get to the operating theatre and not have to worry about equipment and anaesthesia.

“I ensure researchers have what they need,” he says. “I solve the problem from the physical side. They do the biology, I do the physics.”

Greenhouse under construction (left), and ready for use (right), at the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), built with GCP support to boost its chickpea improvement programme. Following its erection in 2013, Asnake Fikre, Crop Research Director for EIAR and former TLI country coordinator of the chickpea work in Ethiopia, commented that “the greenhouse facility will move the programme’s performance forward significantly.”

Once infrastructure such as irrigation and pumps for field trials is in place, it also needs to be kept working. Hannibal says GCP recognised the need for infrastructure, “as well as for maintenance and capacity building of people who operate the systems.”

“That is the safety net of any system,” he explains. “If you don’t maintain it, you don’t have much going.”

The Crops Research Institute (CRI) of Ghana’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) is one of the organisations reaping the benefits, at two of its research sites, of GCP’s infrastructural capacity-building component.

“We got GCP support to kick-start molecular biology research activities,” says Marian Quain, a senior research scientist at CRI. “It provided us with laboratory chemicals, reagent and equipment. My lab also received funding under the Genotyping Support Service initiative to characterise hundreds of sweetpotato, yam and cassava accessions.

“This support from GCP contributed immensely to transforming the lab.”

Meeting the challenges and looking towards the future

Ndeye Ndack says GCP has worked “to ensure that within partnerships, there is respect and fairness among different partners.

“We made sure our national partners had the capacity to move beyond the experimentation, to analyse breeding material and data themselves rather than depend on outside people.

“They are empowered to take advantage of their own data and follow progress within their own breeding programmes.”

She says that to stay successful, “We have to make sure we continue to be responsive so people will continue to adopt and not be discouraged as they might by a team that was not giving them the support they needed.”

The feedback has been very positive.

“What I hear from our IB–MYC trainees is that they feel, year after year, much more comfortable with molecular breeding and with tools like the BMS, and some of them are already implementing these at the level of their team and laboratory,” Ndeye Ndack says.

“Now, of course, the challenge will be to make sure that they implement it beyond these groups, at the institutional and organisational level.”

Jean-Marcel agrees that the final challenge for capacity building was to move beyond GCP support so that the skills and science were sustained in each country: “We needed to facilitate these country breeding programmes to take ownership of the science and products so they could continue it locally.”

He says IBP is playing key a role in sustaining and growing this movement through its regional hubs, which provide training, learning support and networking opportunities.

Leadership within countries will also be vital for the ongoing sustainability of molecular-breeding programmes in developing countries – GCP has helped to create new leaders.

Many of the plant breeders from developing countries have moved from just doing the research, in the early days of GCP, to increasingly taking on active leadership roles in more recent years. More than half of GCP’s projects in its second phase have been led by scientists from developing countries.

Elizabeth Parkes is one such person: she was appointed as leader of Ghana’s GCP-supported cassava research in the second phase of the Programme.

“When I first joined GCP,” Elizabeth recalls, “I saw myself as somebody from a national research programme being given a place at the table; my inputs were recognised and what I said carried weight in decision-making.

“GCP has made us visible and attractive to others; we are now setting the pace and doing science in a more refined and effective manner.”

Over ten years of support, GCP has fostered a new generation of plant breeders, champions and leaders, with the skills and abilities to protect farmers’ futures for many years to come.

More links

- Capacity building blogposts on the GCP Blog

- Capacity building Research Theme